|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Home |

General Information |

Gallery &

Reference |

History

|

News

& Events |

Community

|

Contact Us |

||||

|

| Crescent History | Bath History | Literary Bath | Bath at War| What If? |

|

John Wood's Star By Andrew Swift Reprinted with kind permission from the the Bath Magazine Issue 35 August 2005. (all rights reserved, Bath Magazine 2005). On the northern corner of Alfred Street, there was once a tavern and pleasure garden called the Hand & Flower. Opened some time before 1747, its grounds extended north almost as far as Julian Road, and east to where Saville Row and Russell Street run today. With few buildings to spoil the view, it must have been a wonderful spot. It fell victim to the northward expansion of the city in the 1773. But, if John Wood’s plans for the area had been realised, it might still have been there. In Tobias Smollett’s novel Humphrey Clinker (1771), that archetypal grumpy old man, Matthew Bramble, writes to a friend from Bath: The same artist who planned the Circus has likewise projected a Crescent; when that is finished, we shall probably have a Star. This has always been treated as a joke. But was it? Smollett knew and admired John Wood, who designed the Circus. He also admired his son, John Wood the Younger, who took over the project after his father’s death in 1754. What if there were plans to build a Star? And where would it have been? There are three exits from the Circus. The first leads to Queen Square, the second to the Royal Crescent, the third – nowhere in particular. Shortly after leaving the Circus, Bennett Street kinks to the right and runs along to a T Junction with Lansdown Road. It has been like that for so long, nobody asks why the Woods – those masters of the grand gesture – came up with something so banal.

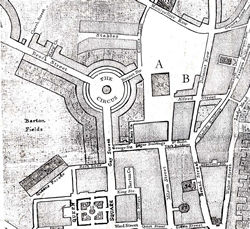

A map of around 1772, showing the Assembly Rooms (A) and the Hand & Flower (B). Even at this date, there was nothing to prevent Bennett Street being extended to the Lansdown Road crossroads to create a Star. The likely answer is that they intended the street to lead to an architectural showpiece to rival Queen Square or the Royal Crescent. If it had continued in a straight line, it would have met Lansdown Road at its crossroads with Julian Road and Guinea Lane – to create a five-pointed Star. The distances from the Circus to Queen Square, the Royal Crescent, and the Lansdown Road crossroads are roughly the same, which suggests that this was planned from the start. And it is a curious coincidence that a pub built just below the crossroads in the 1760s should have been called the Star. Finding a location for John Wood’s Star is one thing; trying to imagine what it would have looked like is much more difficult. The chances are that, like the Royal Crescent, it would have had have had extensive views. Which brings us back to the Hand & Flower grounds. John Wood the Younger may have had his eye on this for building, but it is more likely that he wanted to keep it – as well as the land on the other side of the road – as an open space. It was surely with this in mind that he planned his Assembly Rooms. The new Pevsner Architectural Guide to Bath echoes the prevailing view when it describes the Assembly Rooms as “a large and noble block, tucked away behind the Circus in an unimaginative urban arrangement.” It was not John Wood the Younger’s imagination that was at fault, however. He designed his Assembly Rooms to be viewed from the east. Take away the card room he stuck onto the east end when his grand design had been hemmed in by buildings, imagine seeing it across verdant lawns, and you have a truly imposing building. It was John Wood the Younger’s arch-enemy, Thomas Atwood, who scuppered his plans. Unlike the Woods, Atwood knew how to work the system. He was not only a councillor but also the city architect. Between 1755 and 1775, he built Bladud’s Buildings and the Paragon. Although visible from the Hand & Flower grounds, they did not stand in the way of John Wood the Younger’s plans.

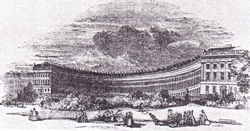

The southern part of Oxford Row, built on the Hand & Flower grounds in 1773. However, between 1770 and 1773, a new terrace – Belmont – was built on the east side of Lansdown Road, blocking the view from the Hand & Flower grounds. The architect is unknown, but it was probably Atwood. Atwood’s next move put paid to John Wood the Younger’s plans altogether. The council owned the freehold of the Hand & Flower grounds. In March 1773, Atwood persuaded them to dispossess the leaseholder, a Mr Rogers, and transfer the lease to him. Within weeks, the grounds were transformed into a building site. Oxford and Saville Rows, the north side of Alfred Street, the east end of Bennett Street, and the east side of Russell Street were the result. All John Wood the Younger could do was to follow the lines Atwood had laid down, continue Bennett Street towards the Circus, and build houses on the south side of Alfred Street and the west side of Russell Street.

The east front of the Assembly Rooms, intended to look out across verdant lawns, is tucked away down a narrow alley. Today, this area, although full of perfectly respectable Georgian buildings, lacks the visual excitement of Queen Square, the Circus, or the Royal Crescent. It is, simply, unimaginative. And while praise for the interior of the Assembly Rooms is matched by lack of enthusiasm for its exterior, its intended façade is hidden away down a narrow alley. How different it could have been if the Woods’ scheme had not been scuppered by eighteenth-century insider dealing. |

|

Copyright 2011 Opus 57 Ltd , All rights reserved Website developed and managed by Opus 57 Ltd |