|

||

|

|

||

|

Home |

General Information |

Gallery &

Reference |

History

|

News

& Events |

Community

|

Contact Us |

||

|

| Crescent History | Bath History | Literary Bath | Bath at War| What If? |

| History

- Literary Bath

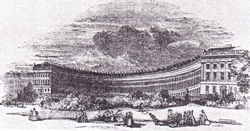

Pickwick in Bath By Stephen Conlin Dickens, as is well known, stayed in No.35 St. James's Square from 1835. He must have absorbed much of the local colour and history; and put these to good use in the passages of the Pickwick Papers set in Bath. None of Pickwick's companions had ever been to Bath. On the morning after their arrival, the Master of Ceremonies comes to meet them, a very dandified and ludicrous figure to whom Dickens gives the name Angelo Cyrus Bantam, and who appears to follow in the steps of Beau Nash. Whilst walking about Pickwick decides that: 'Park Street was very much like the perpendicular streets a man sees in a dream, which he cannot get up for the life of him...' Their first day ends with a ball in the Assembly Rooms, where Dickens sets the social scene, drawing caricatures of the various types to be found in Bath. The: Master of Ceremonies points out: 'The elite of Ba‑ath, Mr.Pickwick, do you see the lady in the gauze turban?' 'The fat old lady? inquired Mr.Pickwick, innocently. 'Hush, my dear sir ‑ nobody's fat or old in Ba‑ath. That's the Dowager Lady Snuphanuph.' Lady Snuphanuph was modelled on the Countess of Belmore (1755‑1841). Lady Belmore lived in No. 17 The Royal Crescent for thirty years, and was indeed an important figure in the social life of Bath, presiding over balls held in the Assembly Rooms. Pickwick goes on to play a bad hand at cards and his partner, Miss Bolo, '...rose from the table considerably agitated, and went straight home, in a flood of tears, and a sedan‑chair.' Pickwick and his friends plan to stay at least two months in Bath and take the upper portion of a house in the Royal Crescent. This provides the setting for a farcical scene when at 3am on a stormy night the bearers of a lady passenger in a sedan‑chair cannot rouse the staff. She and her husband have 'sub‑let rooms from Mr.Pickwick. The, only resident who comes to the rescue ends up marooned on the doorstep in his nightshirt when the front door blows shut behind him. Seeing several ladies approaching along the Crescent, he desperately tries to enter the sedan‑chair. At this point the lady's husband sees what he takes to be the flight of his wife with a gentleman in night attire. The husband and the watchman then pursue the man twice round the Crescent. He eventually runs back into the house and barricades himself in his room, resolved to escape in the morning. 'The ill‑starred gentleman who had been the unfortunate cause of the unusual noise and disturbance which alarmed the inhabitants of the Royal Crescent .... left the roof beneath which his friends still slumbered, bound he knew not whither.' The rest of the stay 'passed over without occurrence of anything material.' Dickens' treatment of Bath is very much of the period. As Bath failed to revive its fortunes in the nineteenth century it was side‑lined into a dull and respectable shadow of its eighteenth‑century self, relieved by the occasional eccentric such as William Beckford. Dickens' attitude to Bath had certainly taken a turn for the worse when he wrote in. a letter of 1869, 'The place looks to me like a cemetery, which the dead have succeeded in rising and taking. Having built streets of their old gravestones, they wander about, scantly trying to 'look alive'. A dead failure!' The reign of Queen Victoria might have seen a revival in its fortunes; if the Queen had visited Bath, or if the Prince Consort had organised some great event here, who knows what might have been achieved for the city? Against this, Victorian economic success could have led too much rebuilding, perhaps even in the style of the Empire Hotel, and one such structure is surely more than enough.

|

|

Copyright 2011 Opus 57 Ltd , All rights reserved Website developed and managed by Opus 57 Ltd |